by Raffy Gutierrez

One of the most exhausting things about living in this country is not corruption alone, or inefficiency by itself. It’s the feeling that nothing is ever complete. Nothing ever truly ends. No problem is fully resolved. No reform is permanently fixed. Everything feels temporary, reversible, fragile—like it can collapse the moment people stop paying attention.

Projects launch, stall, disappear, then reappear under a new name. Offices announce programs, then quietly abandon them. Rules change mid-process. Requirements multiply without explanation. What worked yesterday suddenly doesn’t apply today. Entire department projects are scrapped by the new incoming Department Secretary whenever a new President is elected so that new department projects can be launched. Bagong “pa pogi, pag sipsip.” And when you ask why, the answer is almost always vague: policy change, system update, pending guidelines, wala pang memo, iba ang nasa isip ng bagong President and iba ang gusto ng mga bagong cabinet members niya.

This is not accidental. This is structural. This is a system designed to fail right from the beginning. And it is apparent almost everywhere.

In healthy systems, completion is sacred. Something not completed or even done half-baked is simply not acceptable. A process is not considered done until it actually works for the people it is meant to serve. In broken systems, “done” means approved, announced, or budgeted. Whether it works in real life becomes optional. Whether citizens suffer becomes background noise.

That is why nothing ever feels finished—because completion was never the goal. This is the very root of why the ghost project scandal happened in the first place: that it is possible to report something as completed just by putting the completion on paper and not actually building the project themselves.

We have built a culture where starting things is rewarded, but finishing things is inconvenient. Launching a project earns applause. “Planning meetings” are considered milestones and noteworthy accomplishments. Sustaining actual projects requires discipline. Fixing it requires humility. Admitting failure requires courage. And those last three qualities are often missing where incentives are upside down. It’s almost as if actually building an actual project is considered wrong by the corrupt government officials behind these ghost projects.

So instead of closing loops to complete what needs to be finished, we keep opening new ones and bind ourselves to an unending cycle of things never getting done.

Instead of fixing existing systems, we create parallel ones. Instead of improving processes, we add layers. Instead of simplifying, we complicate. The result is a maze where citizens are expected to remember rules better than the institutions enforcing them. When people get lost, the blame quietly shifts to them: kulang ka sa requirements, di mo nasunod yung proseso, balik ka na lang.

This is how responsibility is inverted.

Technology was supposed to bring clarity and continuity. Instead, it often amplified fragmentation. Different agencies with different systems that don’t talk to each other. Platforms that reset instead of improve. Databases that exist but aren’t trusted. Citizens repeatedly asked to submit the same information because institutions refuse to share responsibility—or data. Technology cannot be used properly because the people behind the technological changes required aren’t true and real technology visionaries.

Every unfinished system becomes another tax on time, dignity, and mental health.

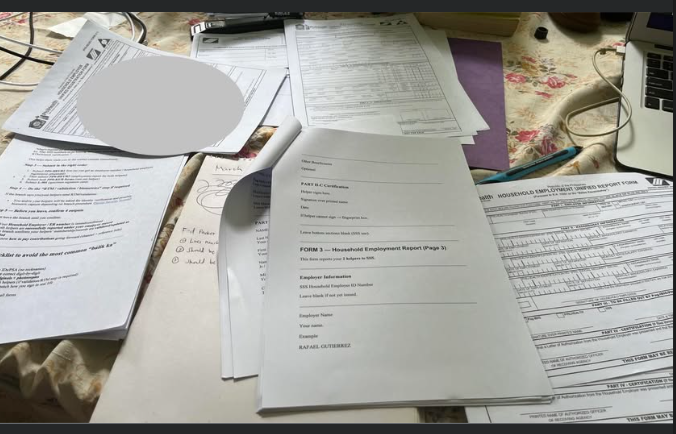

And yet, most people don’t call this out directly. We adapt. We find workarounds. We learn shortcuts. We ask favors. We bring extra documents “just in case.” We build personal survival strategies around institutional failure. Over time, coping replaces demanding. Endurance replaces standards. Many of those who have become tired of the system would rather pay their way through to avoid all the hassle for being compliant. Many more are afraid to speak up because they know that in doing so they could end up finding themselves with a cyber libel lawsuit or even worse.

This is where the damage becomes generational or “normalized.”

Children grow up watching adults normalize waiting, begging, and uncertainty. They internalize the idea that systems are not meant to work, only to be navigated. That progress is personal, never collective. That the safest path is to rely on connections, not competence. Kanya-kanyang diskarte even if it means having to circumvent the rules to get ahead or to get the stuff you need.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: a country where nothing ever feels finished is a country that never truly moves forward. It only circles. It consumes energy without producing stability. It exhausts its citizens while calling it resilience. Kaya nga foreigners who are objective about describing the Philippines say that our country seems to be stuck in the 80s or even earlier decades. Our post office, if we are to be completely brutal, feels like it hasn’t made any real progress since 1945.

Completion is not glamorous. It doesn’t trend. It doesn’t come with banners. It shows up quietly when people stop lining up, stop resubmitting, stop guessing, and stop asking for exceptions. It shows up when rules stay consistent, systems improve instead of reset, and failure is corrected instead of recycled. Completion is silent and subtle but glaring in terms of the people’s feeling of satisfaction, convenience, and thankful that their Government is putting their taxes to good use and not just stolen in “maletas.”

We don’t need more initiatives. We need closure. We need systems that are designed to end properly, not just begin impressively. We need leaders who understand that finishing well is more important than starting loudly and not even making it to first base.

Until we demand completion—not just intention—we will continue living in a country where everything feels temporary, and nothing ever feels trustworthy.

And no nation can mature on unfinished business alone.

__________________

Rafael “Raffy” Gutierrez is a Technology Trainer with over 25 years of experience in networking, systems design, and diverse computer technologies. He is also a popular social media blogger well-known for his real-talk, no-holds-barred outlook on religion, politics, philosophy.