By Raffy Gutierrez

For decades, Filipinos have been lauded for resilience, tenacity, and contentment. We smile through knee‑deep floodwaters, rebuild after storms, and tell ourselves “bahala na” – what will be will be. These virtues have helped communities survive, but they can also be misused. When resilience turns into passive acceptance, it can mask systemic failures, discourage us from demanding accountability and allow unjust systems to persist. In this way, virtues meant to strengthen us can be wielded to excuse the neglect of our dignity, welfare, and safety.

The Philippines has battled seasonal floods for nearly half a century. Every rainy season brings stories of lost lives, ruined livelihoods and families huddled on rooftops or in overcrowded evacuation centres. Even without typhoons, heavy monsoon rains routinely turn streets into rivers. Floods and storms are expected to cost the country an estimated $124 billion by 2050, yet many Filipinos have grown accustomed to this annual ordeal.

In his third State of the Nation Address in July 2024, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. proudly reported that more than 5,500 flood‑control projects were completed from July 2022 to May 2024, with over 5,000 more under construction. Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) Undersecretary Cathy Cabral explained that without these interventions, recent rains would have caused even more severe flooding. However, DPWH Secretary Manuel Bonoan later told senators that these completed projects were “immediate relief” measures, not part of a comprehensive plan. An editorial in the Philippine Daily Inquirer noted that despite spending roughly ₱1.2 trillion on flood control since 2009, the country still lacks an integrated master plan and the ₱351‑billion Metro Manila flood‑control blueprint approved in 2012 is only about 30 percent complete.

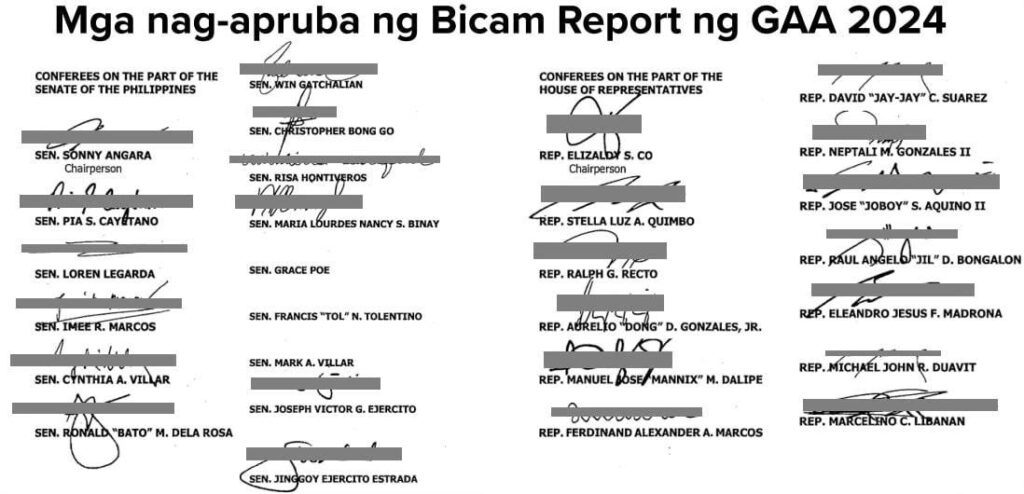

International reporting paints a similar picture. Al Jazeera observed that, although the Marcos administration has allocated about half a trillion pesos to flood‑control efforts and announced the completion of over 5,000 projects, government data show that only one of the “flagship” projects was finished in 2024 while others remain in preparatory stages. The DPWH admitted that 70 percent of Metro Manila’s ageing drainage system is clogged with rubbish and silt, and there is no national flood‑control master plan – only 18 scattered plans for major river basins. Independent budget analysts told Al Jazeera that flood‑control funds are often inserted at the last minute during budget deliberations, making the projects vulnerable to “patronage politics” and difficult to monitor. Lawmakers and advocates have called for the Commission on Audit to scrutinise these projects for possible misuse and for greater transparency in how climate‑adaptation funds are spent.

Here is where virtue becomes a trap. In a commentary titled “Address toxic resilience now,” former Development Bank of the Philippines executive Benel D. Lagua recounts how media coverage often praises flood victims for laughing through waist‑deep waters instead of asking what government ineptitude and corruption allowed the floods to happen. He argues that constantly celebrating resilience can lead to complacency about systemic problems such as corruption and governance failures. Cultural values like “bahala na” and “pagiging matatag” encourage endurance but can discourage proactive problem‑solving. Sociologist Randy David has observed that this tendency to “move on” from scandals fosters cycles of corruption and injustice.

Critics say that such “toxic resilience” benefits those who profit from the status quo. When citizens quietly endure hardships, there is little pressure for leaders to fix ageing drainage systems or deliver promised infrastructure. Flood‑control projects have become a lucrative line item in the national budget, yet many remain unmonitored and unverified. This does not mean ordinary Filipinos are to blame for flooding, but it does show how our celebrated virtues can be manipulated to justify neglect. It’s sad that virtues that should have been the reason why we can become a great nation instead justify persistent corruption in the Government.

How can we turn resilience from a coping mechanism into a catalyst for change? Lagua and other scholars argue that education, critical thinking and active citizenship are essential. Communities must demand transparency on where flood‑control funds go and insist that projects follow comprehensive plans. Electing leaders with integrity and holding them accountable is crucial. Strengthening institutions, ensuring open procurement and empowering agencies like the Commission on Audit to investigate misuse can help restore public trust. Resilience should not mean accepting substandard services; it should give us the courage to confront the root causes of our suffering.

There is still room for hope. The government has acknowledged problems in flood‑control spending, and there is growing public awareness of how climate change and rapid urbanisation exacerbate floods. Modern engineering approaches, such as “sponge city” designs that allow water to soak into the ground rather than funneling it away, could be adopted. But real progress will require both leaders and citizens to see resilience not as an excuse for inaction but as a drive to build a society where floods are managed effectively, funds are spent transparently and every Filipino can live with dignity.

Only Filipinos can decide whether to keep enduring indignity under the guise of “resilience,” or to wake up and insist that those in power be held accountable.

———————————————————–

Rafael “Raffy” Gutierrez is a Technology Trainer with over 25 years of experience in networking, systems design, and diverse computer technologies. He is also a popular social media blogger well-known for his real-talk, no-holds-barred outlook on religion, politics, philosophy.