📷: The late veteran journalist and political analyst Julius Fortuna.

by Diego Morra

It was unexpected but film director and actor Joel Lamangan paid tribute to Julius F. Fortuna, commissar to his colleagues at the defunct Daily Globe, once an officer of the National Press Club of the Philippines (NPC), a pillar of the pre-martial law Movement for a Democratic Philippines (MDP), organizer par excellence and champion of political prisoners and defender of overstaying residents of the National Penitentiary in Bilibid, when he delivered his remarks on politics and culture during the 40th anniversary of the Bagong Alyansang Makabayan at the KAL Theater in UP Diliman on Jan. 14, 2026.

Lamangan spoke glowingly of Julius, originally from the University of the Philippines at Diliman, Quezon City before shuttling off to Lyceum of the Philippines, the hub of student protests in Manila, a school where Jose Ma. Sison taught, and where hordes of student activists congregated in the years before “Philippine Society and Revolution” (PSR) was yet to be published in one volume. Originally entitled “Philippine Crisis” carried by the Philippine Collegian under the editorship of Ernesto “Popoy” Valencia in 1970.

The film director noted that it was Fortuna who tackled comprehensively the dialectic of politics and culture, dismantling the idea that both inhabit their vacuums, never entangled and with no relevance to each other, recalling how Salvador P. Lopez also smothered the idea of art for art’s sake decades earlier. Only a fraction of the large crowd at the Ignacio Gimenez Theater that night must have known Julius, including a surgeon who is also in the business of curing a sick society, as well as director Boni Ilagan, of “Pagsambang Bayan” fame, poet, singer and artist Jess Santiago and, of course, Satur Ocampo and Bayan chairwoman emeritus Dr. Carol Pagaduan Araullo.

Julius, who confessed that his baptismal name was Brando Julius, hied off to parts unknown in the wee small hours of the morning in June 2009, hours after complaining of shortness of breath. Dr. Fernando Melendres, a friend to all the members of the Alps coffee club like the late Harvard-trained lawyer and economist Alejandro “Ding” Lichauco, was dumbfounded. Dr. Melendres, a cardiovascular surgeon, said had he been consulted, the clogging could have been eased even if Julius were actually preparing for another procedure. Julius wrote a column for the Manila Times, “East and West,” and hosted the weekly news forum Kapihan Sa Sulo Hotel every Saturday in Quezon City when he passed away. He was also a regular at the Ciudad Fernandina forum hosted by the late Ambassador Noel Cabrera.

A friend to many, Julius was crucial to the expansion of the MDP and the formation of various organizations that defended human rights and civil liberties as the Marcos Sr. regime moved to stifle dissent with the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus in 1971 and the eventual imposition of martial law in September 1972. He was imprisoned and subjected to the worst interrogation tactics pioneered by US-trained intelligence officers. Like the great organizers Monico Atienza and Leoncio Co, he learned more about their tormentors and their weaknesses. Prison walls merely restricted them but their tongues and hearts were unchained, thus dismissing the idea that those incarcerated were “politically dead.”

Under his tutelage, a number of journalists survived the travails of the beat, learned the ropes, so to speak, and understood what the German minister Dietrich Bonhoeffer meant when he said “silence in the face of evil is itself evil: God will not hold us guiltless. Not to speak is to speak. Not to act is to act.” Samahang Plaridel, an organization of journalists of which he was vice president and charter member, mourned his demise, saying his passing was a profound loss to Philippine journalism. A native of Odiongan, Romblon, Fortuna was much sought-after by local and national leaders for his analytical mien and his ability to solve nagging issues that split political forces and prevent them from forging ahead.

Friends remember him fondly for being busybody, with the late Joe Cardenas relating that in his haste, he would wear different socks, with the left sock not agreeing with the right sock. He was always properly dressed, bringing a bottle of two for discussions at UP Bliss in the company of Caloy Ortega, the worker who could smother any national master in chess at the Ipil Reception Center in Ft. Bonifacio, Nick Atienza and Malaya editor Joy de los Reyes. Unknown to many, Julius also played a role in mediating disputes even within an indigenous church. His many admirers went to the extent of using his name as their noms de guerre or noms de plume during the dictatorship and beyond.

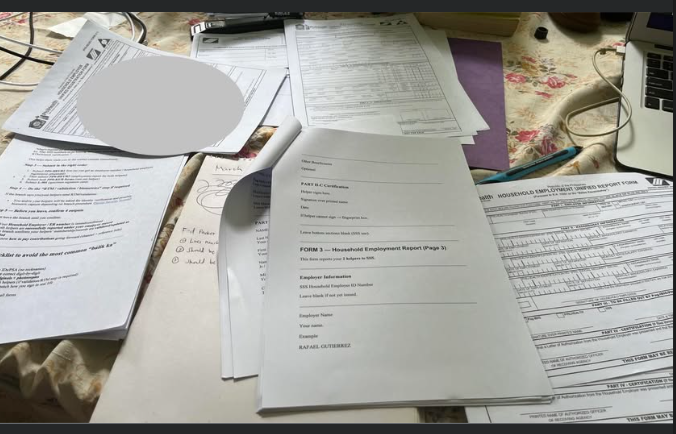

Erlinda Taruc Co remembered meeting Julius after two decades and during the animated conversation, Julius made quick hand gestures as if he were holding a conductor’s wand, and he lost his dark glasses that went straight into a canal. “Sa lalim at dilim nito ni hindi man lang namin makita. Natawa lang siya,” Linda recalled. Julius also lost something more valuable one time. His box-type Mitsubishi Lancer with plate number PCZ 353 disappeared from his parking slot at the Pag-Asa Bliss. No one noticed the carjacking despite the huge number of residents at the back of SM North EDSA. This is the same Julius whose library loses a book or two when friends visit him, or work in a desk crammed with documents. He is the same Julius who tackled the serious issues of 1992 and rejected those who rejected the revolutionary project.