For decades, the advice to “eat three balanced meals a day” has been the gold standard in public health. From government dietary guidelines to school health classes, this simple prescription was meant to ensure steady energy, prevent overeating, and maintain overall well-being. But recent research into fasting, circadian rhythms, and gut health has challenged the idea that three square meals should be the universal rule. The truth is more nuanced—both science and common sense suggest that how and when you eat matters just as much as what you eat.

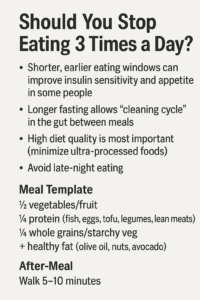

One of the most intriguing findings in recent years revolves around the migrating motor complex (MMC), an internal housekeeping cycle in your digestive tract. The MMC acts like a cleaning crew, sweeping away undigested food particles and bacteria between meals. But here’s the catch—it only operates in a fasted state and stops every time you eat. This means constant snacking or tightly spaced meals can interrupt the gut’s natural cleaning cycle, potentially contributing to bloating, bacterial imbalance, and slower digestion.

The concept of gut rest ties closely to intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating. In clinical trials, limiting eating to shorter daytime windows—say, between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m.—has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, lower blood pressure, and even reduce appetite in certain groups. These benefits occur even without weight loss, hinting at metabolic advantages tied directly to when you eat. This isn’t about starving yourself—it’s about allowing your body enough downtime to carry out maintenance and repair processes.

But let’s be clear—reducing meal frequency isn’t automatically healthy. Your body still needs essential nutrients, especially protein, vitamins, and minerals, to repair tissues, build muscle, and support your immune system. For older adults, the risk of muscle loss is especially high if protein intake is inadequate. The recommended daily allowance is about 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, but experts suggest 1.0–1.2 grams for older adults to maintain muscle strength and function.

Another important layer in this conversation is diet quality. Studies comparing ultra-processed and minimally processed diets—matched for calories, sugar, and fat—found that participants on ultra-processed diets ate roughly 500 calories more per day without realizing it. This points to a simple but powerful truth: even if you eat fewer meals, if those meals are packed with refined carbs, added sugars, and industrial oils, your body will struggle to thrive. A nutrient-rich, minimally processed diet remains the cornerstone of health, regardless of meal timing.

There’s also the issue of late-night eating. Research into circadian rhythms shows that our bodies process food less efficiently in the evening. Calories eaten late are more likely to be stored as fat, and glucose regulation is impaired. In other words, the same meal at 10 p.m. will spike your blood sugar more than if you ate it at 6 p.m. This is why many time-restricted eating studies focus on earlier eating windows, aligning meals with the body’s natural metabolic clock.

So where does that leave the “three meals a day” model? For some, especially those with high energy demands—such as athletes, pregnant women, or people with certain medical conditions—three meals or even more may still be ideal. For others, particularly those looking to improve metabolic health or manage weight, two main meals and a small snack within a 10-hour daytime window might be a better fit. The key is tailoring the approach to your lifestyle, goals, and health status, rather than blindly following a one-size-fits-all rule.

An often-overlooked tip that pairs perfectly with meal timing is light physical activity after eating. Even a five to ten-minute walk after meals has been shown to blunt post-meal glucose spikes, improve digestion, and enhance overall blood sugar control. This is a low-effort habit with outsized benefits, especially for people with prediabetes or insulin resistance.

What about fasting for “detox”? While fasting does trigger a process called autophagy—a form of cellular recycling—this isn’t the same as the marketing-driven idea of “cleansing” popular in fad diets. Your liver and kidneys handle detoxification 24/7, regardless of whether you’re fasting. The real benefits of strategic fasting lie in metabolic improvements, gut rest, and appetite regulation—not flushing out mythical “toxins.”

If there’s one unifying message, it’s that meal timing is a tool, not a cure-all. Think of it like exercise: you can get benefits from many forms, but results depend on consistency, personalization, and pairing it with other healthy habits. Eating nutrient-dense whole foods, avoiding excess sugars and processed snacks, staying active, and aligning meals with your body’s rhythms will do far more for your health than rigidly cutting down to one or two meals without considering food quality.

In the end, the debate isn’t really about whether you should eat two, three, or six times a day. It’s about reclaiming intentionality in how you fuel your body. Our modern food environment makes overeating—and especially over-snacking—far too easy. By rethinking not just what we eat, but when and how often, we can harness both modern science and timeless eating patterns to support long-term health.

Hopefully, this article will shed some light on that now-trending “You should not eat three times a day” meme.

———————————————————–

Rafael “Raffy” Gutierrez is a Technology Trainer with over 25 years of experience in networking, systems design, and diverse computer technologies. He is also a popular social media blogger well-known for his real-talk, no-holds-barred outlook on religion, politics, and philosophy.